General News

26 June, 2024

It’s complicated: North West has a tricky relationship with nuclear

A look at the long history our region has with uranium and nuclear energy

There has been a radioactive glint to public debate following the announcement that a future Coalition government would build seven nuclear reactors at the sites of retired coal power plants across five states of the nation.

And while much public debate centres on the viability of building small modular reactors versus the rewiring of Australia’s energy system towards wind and solar energy, any growth in nuclear or renewable technology would see the North West continue its long standing contribution to keeping the economy powering forward.

The Coalition announcement has fuelled some discussion for the return of uranium mining.

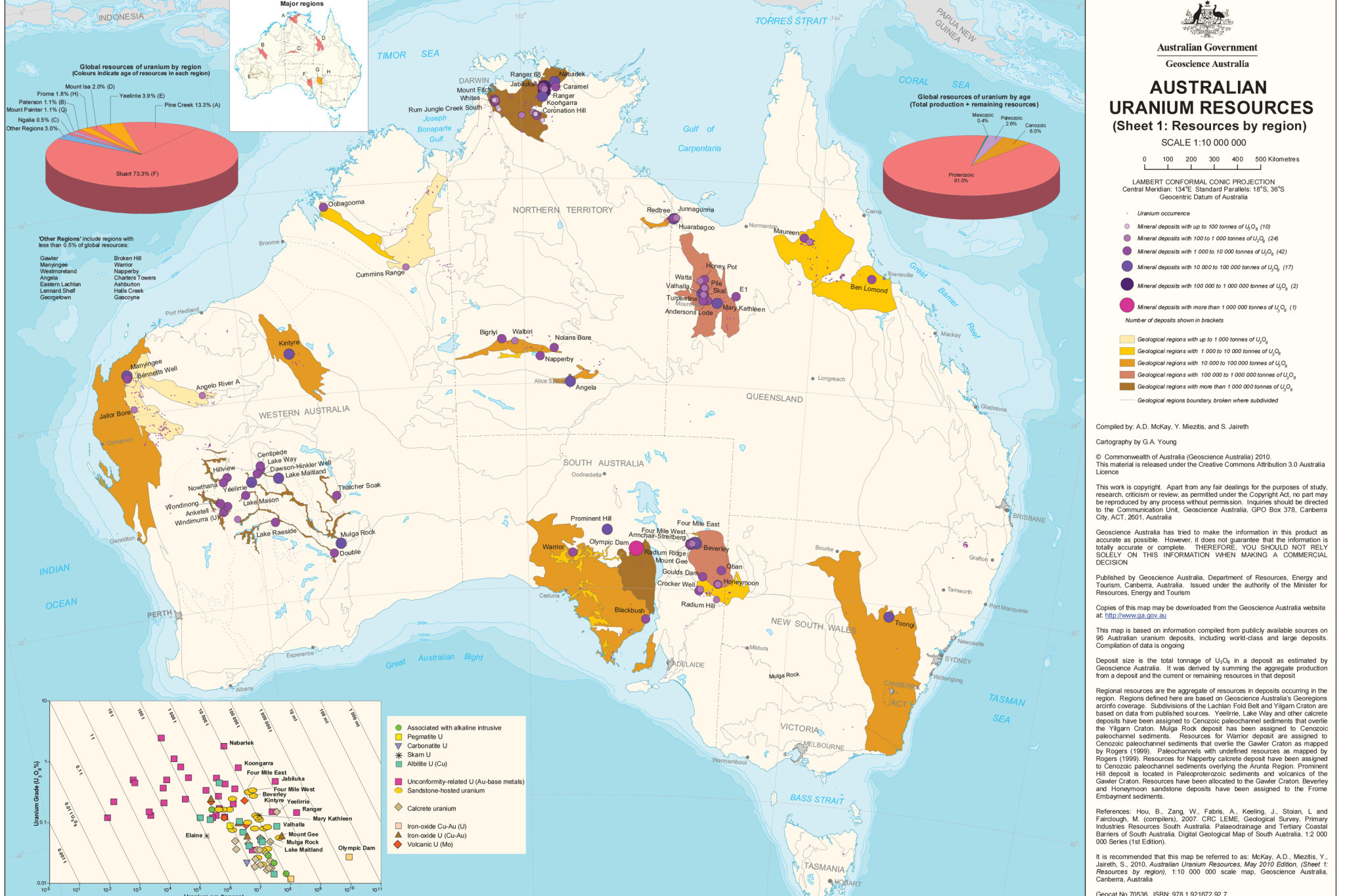

Hosting the largest amount of recoverable uranium – much of it surrounding Mount Isa and Cloncurry – Australia has often been called the Saudi Arabia of the field.

As the latest chapter in the energy wars is being written in Canberra, it is worth turning back the pages to remember the North West’s colourful relationship with yellowcake.

Uranium fever first struck Mount Isa in March 1954 after a syndicate discovered the first radioactive specimens near Gunpowder, with the claim quickly pegged and named Skal – Swedish for ‘good luck’.

This was a somewhat ironic title given uranium had been labelled globally as a “bad luck rock” for decades prior, because it had no discernible use for most of its history, and was found where the silver trails ended at mine sites.

Within days of the Skal discovery, the countryside was littered with mineral hunters scouring the rocky hills and outcrops hoping to strike it lucky.

Stores sold out of Geiger counters, which had replaced the traditional prospecting pans during this mining rush, as rumours about the next big eureka moment burned brightly across North West pubs.

This frenzied atmosphere also brought tall tales that make for interesting reading decades later.

There were newspaper columns written at the time that claimed a cockatoo had been taught to eavesdrop on hotel conversations and repeat its hearings back to its owner as well as talk of a ‘radioactive’ wild pig that produced high readings on the geiger counters, leading desperate prospectors to follow the boar through the miles of scrub, expecting it would lead them to a uranium El Dorado.

Dead-end bush tracks became clogged with prospectors stalking the latest claims; planes flew at questionable heights above the diggers as geologists experimented with new methods to sight the uranium patches.

The hills at some tenements were said to faintly glow at night- apparent evidence of radioactivity.

Eventually a Mount Isa Mines underground timberman and a taxi driver punctured a tyre down by an isolated creek – the geiger counters started screaming at the pair and they soon realised they had struck buried treasure.

The eight-man syndicate had uncovered a mountain of radioactive ore. Within months, experimental drilling was underway and soon tents lined Green Creek as an open-cut uranium mine took shape.

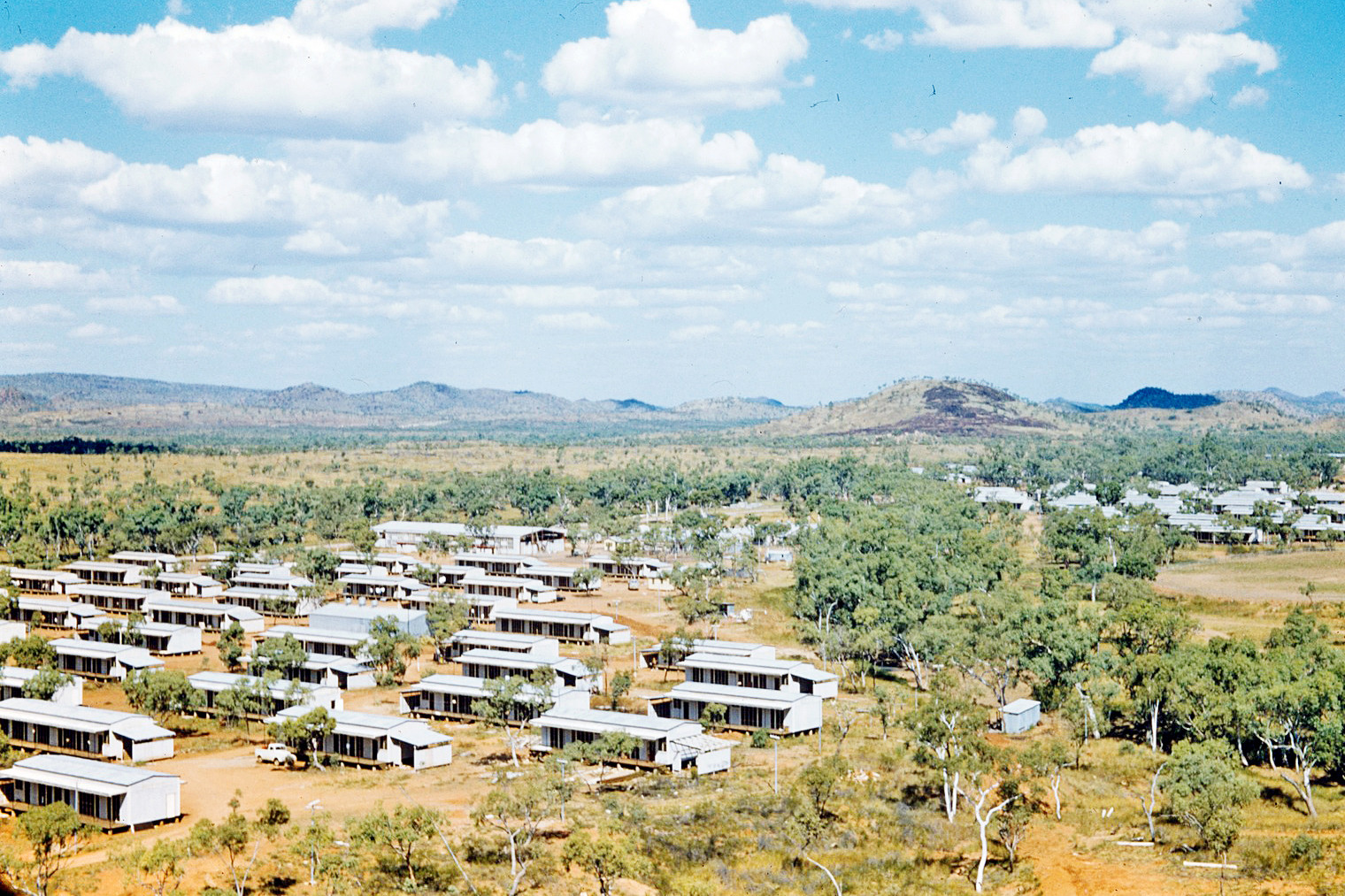

Less than three years later, a township stood where the canvas humpties once sat, with its six-bed hospital, open air cinema, barber shop, community store and 29-acre market garden.

During the 1958 election campaign, Prime Minister Robert Menzies unveiled a plaque to officially give birth to Mary Kathleen uranium mine and township.

“Mary Kathleen doesn’t exactly loom on the horizon, it sort of appears, shyly, from behind two mounds,” a journalist wrote.

Named after Mary Kathleen Brown, the recently deceased wife of one of the original tenement owners – who lies buried at Sunset Lawn cemetery – Mary K’s similarly short life would become a celebrated example of Outback community – a “Garden of Eden” as one resident called it.

It would also be rocked by international headlines, litigation and scandal – all the while being, at times, the sole contributor to the only uranium boom in Australian history.

The first phase of the mine’s operation covered one large contract with the British Atomic Energy Commission, which was complete by 1963. However, the development of civil nuclear power stimulated a second wave of exploration activity in the late 1960s, with Mary Kathleen recommissioning its mine and mill in 1974.

It was a time when the Vietnam War movement had turned its ire towards the threat posed by nuclear holocaust – a protest movement aligned with the Whitlam Government, which oversaw inquiries into uranium mining and trade.

At the same time, industrial action was taking place at Mary Kathleen. The Railway and the Seaman’s Union placed a ban on some material being transported from the township due to concerns for worker health and safety.

A young Paul Keating was driven by a younger Tony McGrady from Mount Isa to Mary K.

There was a swirl of protesters surrounding the vehicle that had placed a padlock on the entry gate, preventing access.

Unperturbed, the future Prime Minister set aside his jacket and climbed the fence, trading colourful insults with the throng of demonstrators.

Amidst the industrial turmoil, a disgruntled worker leaked a 200-page report about Mary K operations to environmental activist group Friends of the Earth.

The report sensationally revealed the Mary Kathleen operators had been involved in an international price fixing cartel called the ‘Uranium Club’.

The scheme across more than five countries saw cartel members skirt around international treaties, sell to outlawed states and deliberately inflate global prices.

Some of the biggest corporate buyers of uranium, none too happy they were paying a price inflated by ten-fold, sued mine operators across the globe, forcing payouts edging $1 billion – placing a significant financial strain on the Mary Kathleen organisation.

In 1980 it was revealed that an Australian uranium mine had lost 2200kg of uranium oxide.

The trail led investigators to Mary Kathleen. A former worker was found to have secretly filled six drums over a 12 month period and smuggled the material out of the processing plant.

He was only caught when he turned up in Sydney, hoping to sell it to a shocked scrap merchant.

The man was found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison in 1981. The story fuelled fears of uranium falling into the hands of bad actors and terrorist groups.

It was 1984 when Mary Kathleen completed its transformation into Queensland’s latest ghost town – 500 jobs were lost, 1000 people lost their homes, which was one-third of the Cloncurry Shire at that time and $1 million a month in wages also disappeared.

As uranium and nuclear fever once again returns to the national spotlight, much can be learned from the hard fought battles the North West has endured in decades past.

Building a national nuclear strategy will require technological innovation, regional planning, industrial agreement, environmental safeguards and a bit of digger’s luck – all factors that shape the story of the North West and its previous uranium experience.

Reminders of what has come before will help plan what might be in the future.